On the 27th of August 1883, an Indonesian island was vaporised in an explosion that reverberated around the world. Krakatoa, located in the Sundra Straits between Java and Sumatra, decided to sign off with a blast that flattened the 23 square km island and then some; in fact it took off another 250 metres of land below sea level. The bang, equivalent to 21,000 decent atom bombs, could be heard 4500 km away, and sent so much ejecta into the atmosphere that the entire planet enjoyed spectacular sunrises and sunsets for several years afterwards – the trade off for copping a global drop in temperatures of a couple of degrees.

Not unexpectedly, the explosion also generated ferocious tsunami waves, some of which measured over 100 feet high. They slammed into west Java and Sumatra, including one straight shot, thousands of kms up through the Indian Ocean into south facing Lagundri Bay, on the island of Nias. In those days Lagundri Bay was the main port of south Nias, and the massive tsunami killed thousands of people in the bustling harbour and surrounding villages. The port was never rebuilt at Lagundri, eventually being re-established a few kilometres to the north-east in Teluk Dalam, leaving Lagundri a quiet backwater.

That wasn’t the first tsunami to hit Nias, and wouldn’t be the last. The island sits in prime tsunami territory, 125 km off the West Sumatran coast in the vicinity of the Sumatran Subduction Zone, the 5500 km long boundary between the Indian-Australian and Eurasian tectonic plates. This boundary runs along virtually the whole of the west coast of Sumatra, the plates meeting at a fault about 5 kms under the ocean in the Sumatra Trench, a couple of hundred kms off the coast. Here the Indian-Australian plate is forcing its way under the Eurasian plate. It is one of the most seismically active places on earth, and it has plenty up its sleeve.

Although I’d been to Nias a few times before, it had sure been a while. And a good long while before the creation of the ‘new’ reef. The talk of the altered state of play at Lagundri had been driving me insane. I knew there was a change in the wave due to uplift from the March 28th earthquake, and the consensus was that it was for the better. Better? Better than the most airbrushed and flawless big tube you could imagine? What would be the odds? I couldn’t help but think there was more tall tale than truth to the rumours, a real possibility since Indonesia is gossip central of the surfing world. The intrigue was just too much. I had to know, and I managed to convince a couple of mates, Joe Haddon and Ben Godwin, to come along and find out with me. Both from Forster, Joe is a stylish natural footer with a perpetual grin, a great traveller who is a genuinely happy person. Ben is a tall goofyfoot, a lanky larrikin aerial type maniac, who has really hit a new level in his surfing over the past year or so. He’s a classic old soul, busting out a string of hilarious narrative, punctuated by a durry, when you least expect it, and regularly bringing the house down at dinner.

Twenty two years after I first went to Nias, it’s no easier, or quicker, to get to from Oz, especially if you miss out on a seat for the Medan to Gunung Sitoli [Sumatra to Nias] flight like we did. Our only other option was a flight to Sibolga to grab the overnight ferry to Teluk Dalam, in the south of the island. This led to our first pressure situation when some Medan airport urchins assured us, despite the fact that we knew it was booked out for three days ahead, that they could get us tickets for the “full” flight to Gunung Sitoli. I should have known better, but we were just off our third flight in 24 hours. We were hassled and harried, and melting in the equatorial heat, and had to make a quick decision via my retarded Bahasa; we said: “ok, get the tickets.” It was corrupt Indonesia after all, and full didn’t always mean full. After much hustling and running around, and with the clock ticking, the urchins came back and said: “no, we can’t get on today’s flight, but tomorrow can, can!” After more sweating, we finally pulled the pin on it, we couldn’t risk missing out again tomorrow. The boys looked as if they’d had a gut full of Medan already, but we had to get our shit together; with only 15 minutes to buy tickets and get on that flight to Sibolga. We were going old school.

After landing at Sibolga, as low key a shearing shed of an airport as you could imagine, we went with the flow of the local grifters. It felt right, sometimes it just does. Nearly everyone is on the grift in Indonesia, at least when it comes to western tourists. It’s done in the mellowest and friendliest way though, and they rarely rip you off, not really, it’s usually just a small commission style earn. Minor, unless you are in the weird thrall of the rupiah syndrome, forgetting that the thousands you haggle over are actually mere cents, and the thought of paying a little more than some other hard case bargainer is painful to you. These ultra tight arsed travellers do turn up, and it is bizarre how much time and energy they will devote to saving what often amounts to 20 cents. In Indonesia, everything costs something but nothing costs much, and sometimes I think time is more valuable than a handful of rupiah. Its best to just shed a steady rain of bank notes and coast along — most Indonesians earn peanuts and it doesn’t really hurt your wallet much — and things seem to flow smoothly. We moseyed on to a bemo and eventually found ourselves at an old hotel bar, with new mate, Peter of Sibolga, immediately on the case. Icy Bintangs, arrangements for tickets on the overnight ferry to Nias, and even a hook up for accommodation with his mate Raffiel at Lagundri, were ours in an instant.

“He’ll even pick you up from Gunung Sitoli!”, Peter said triumphantly, but I was shocked. “Hang on . . . What? The ferry doesn’t go to Teluk Dalam?”, I pleaded. Teluk was in the south, a half hour drive to Lagundri. Landing at Gunung Sitoli in the north meant a three to four hour drive down the island, on top of the 12 hour ferry trip. He laughed and shook his head. I just laughed too, and started looking for my Valium. Ben and Joe were thriving on it, this was real Indonesia, way beyond Bali, and it even looked like there was a bit of swell coming. I put the old horror stories of ferries being cancelled due to large swells — surely the ultimate surfer nightmare — out of my mind, as we headed for

Sibolga Harbour late that afternoon. We’d be in Nias in the morning.

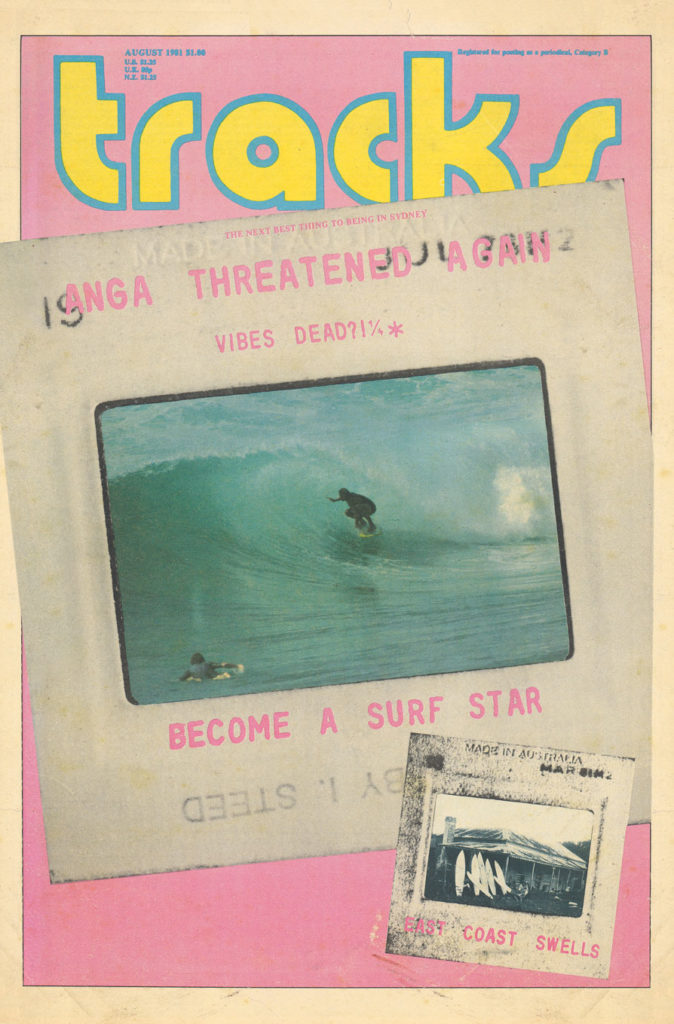

Joey Haddon in the hole, not at Nias, but another of the quality, secret waves in the area. Photo: Dave Sparkes

Joey Haddon in the hole, not at Nias, but another of the quality, secret waves in the area. Photo: Dave SparkesIn 1987, my first sight of Lagundri Bay was almost straight out of some spacey ‘70s surf flick. I was travelling solo, planning to meet my brother Hazy, who had arrived a week before. As the bemo sped along the coast road towards the Bay, fleeting gaps in the coconut groves revealed flickering, on/off movie reel vignettes of the sea. Suddenly we went past a clear patch, and there across the bay, presenting as a still frame, was the almond eye of a beautiful, big right hand tube. The blinding white foam around it looked bleached and overexposed from my perspective in the shady jungle. The wave looked at least double overhead, and it stayed around that size for three weeks straight. There was an eclectic crew of 20 odd travellers there. Most of them had got to Nias via drug crops or smuggling scams or other shady goings on. There were a couple of professional Asian circuit types: score hash up in Thailand or India, bring it down through Indonesia, selling it on the way, finish in Bali for some party time, head back up and go again. Some of these guys never went home, hadn’t for years, and some of ‘em are probably still lurking around Indo pulling the latest scams. There was a crew of mad Kiwis, one of them was a freaked out industrial chemist who was making liquid speed on the point. Mushies were going down like hotcakes, and the waves just didn’t stop. Most of the crew were good surfers, full tube junkies on missions, and the lineup was always competitive. Except for one windless five foot afternoon, when Hazy and me surfed alone after a very a mild cup of mushroom tea each. You reckon the Lagundri lineup looks trippy at the best of times? We thought we were on Saturn, man.

Everyone was having weird dreams, and often a few guys would have the same dreams as each other! The buzz was that the Krakatoa tsunami had killed thousands of locals, and few of the proper burial rites had been performed, leaving the place haunted. Years of Indo experience later, I realise it was probably malaria prophylactics causing the dreams, but don’t get me wrong, the vibes can get strange on Nias. There weren’t many locals surfing then, Peruba and Sonali were about it. Even then, Sonali was the master of the inside runner, and got the longest tubes of anyone. It seems like those slightly smaller- than-set waves are always the hollowest, wherever you go.

Another memorable trip went down in 1994, when underground Indo veteran, Zeegs and me turned up wobbling after a horrendous cargo ship ride out from Sibolga during a massive swell. We showed up at the Bay next day with rubber sea legs and goggle eyes, watching eight to ten foot walls reel unclaimed down the point. For the first week, there were only four guys on it, and didn’t that 7’6” Pang do the trick! A few more locals surfing too this time, with a bunch of groms ready to step up.

The signature deep, green water colour, long ramping wall and palm-fringed background of Nias blowing the back out of it. Photo: Dave Sparkes

The signature deep, green water colour, long ramping wall and palm-fringed background of Nias blowing the back out of it. Photo: Dave Sparkes“How will this Raffiel guy know who we are?”, Joe wondered as we pulled into Gunung Sitoli harbour around five next morning. We were completely fried from a sleepless, hideous all night grovel on the ferry. It was packed out with humans, and in eventual desperation I had taken more valium and just flaked on the floor. I woke an hour later lying in a puddle of Indo Mie slops and soggy Gudang Garam butts, and looked up to see Joe and Ben in foetal positions, huddled in plastic chairs and preying desperately for dawn to come, and with it release. Don’t let anyone say you don’t earn Lagundri.

“He’ll know, don’t worry. When there’s an earn involved, they don’t miss a trick, just kick back and let them come,” I said with all the airs and graces of a know-it-all arsehole Indo legend. But sure enough, we weren’t even off the ship when a guy came up, patting us on the back: “Peter of Sibolga is my friend. I am Raffiel! Mr Dabid Sparkez? We go!”

The main road down the 120 km long island is much improved, but Raffiel drove like a maniac, and that’s on Indonesian ratings. He is definitely the most hardcore I’ve ever seen, going through narrow village roads at a velocity that rendered the stunned passers by, from our point of view in the van, as flashing blurs of colour. The trip down the east coast is a scenic one, even in fast motion, with lots of little coves and headlands, bays, escarpments and rivers, and actual bridges, not like the MacGyvered, improvised logs and girders of the past. I was losing it at the thought of seeing the point again, and when we finally turned to drive into the Bay, I could see Joe and Ben straining for a glimpse of it. I thought back to that mental still frame of my first view, and hoped they’d see something like it, and maybe they did. There were definitely waves, and as we pulled into Raffy’s losmens, a clean five foot wall reeled across the reef and spat out way down the end, leaving a cloud of mist that temporarily obscured the impossibly exotic, surreal Lagundri backdrop. Well, that wasn’t bad for a first look.

While we were marking out territory, chucking gear into rooms and boards into piles, I heard an unmistakable Seppo voice:

“Hey Sparrrrkes, what’s up you fuckerrrr?!” I looked out and saw Jamie O’Brien and his hilarious sidekick, Ruben, lounging around amidst piles of food, looking like lords of muck.

“Jimmie! Oh no, Ruben you freak, yeah boys!”, I said, still surprised.

I’d shot Jamie a lot back in his grom days and had seen what he can get up to with a hollow wave. It was a little bonus for me photographically, but Joe and Ben were even more stoked after intros were made and it emerged that we’d be rolling with Jamie for a while. He would be around for a week or so and had already invited the boys to go and surf another spot with him right now, grab ya stuff and let’s go! So with barely another look at Lagundri we drove for quite a while before checking some short but very surfable reef options, finally stopping at the funnest looking three-to-four foot right wedge to wall I’ve ever seen. I realised I’d surfed it years before from a boat, but had never seen it from the land. Maybe it had changed; it seemed like a much better wave now. There was no one out. The boys were in a fever, I don’t know if it was first surf froth or the thought of surfing with Jamie, but I couldn’t blame ‘em, it looked pretty inviting. The wave stands up in a peak and then bends and slingshots down the line, throwing up tubes and ramps in varied combos, and occasionally growing as it runs through the inside. It immediately becomes everyone’s favourite.

Ben and Joe get on well with Jamie. They get on well with every traveller we run across, and even tolerate my Steely Dan obsession and old fart “shoulda been ‘ere fifty years ago” tales. Ruben is on fire. He is about 5’2” and is basically a mouth on legs. It never stops, and regularly gets him into trouble; he just has to have the last word. When not in the tube or the air, Jamie spends most of his time kicked back laughing at Ruben’s escapades. He looks like a mini Buttons, and basically travels around with Jamie, filming him and writing him off and generally mucking up. The guy is a classic, he’s like a little one man party. The Indonesians love him, constantly in hysterics at his endless monologue. He rips right into me, being tall makes me a prime target, and we are often at it tooth and nail; the full Foghorn Leghorn and Chicken Little act.

The waves stayed a steady four to five foot for the next week, and the boys were pigs in shit, feasting on the fun walls, and getting inspired by Jamie’s futuristic attack. At Lagundri, the change in the reef was quite obvious. Previously at this size, the wave did break but it was a tease, a brief gorgeous face that left you wanting more as the wall rapidly dissipated after your first turn. Any smaller than head high and it didn’t break on the outside at all. Now it was at least twice as long, and even offered barrels, although they are very tide dependent. The lineup seems more complex than it used to be, with a bit more variability from wave to wave. It is definitely an improvement at this size, and I wondered how it would be at six-to-eight foot? Time was limited and I just prayed we’d see it like that. It is hard to imagine it any better at six-foot-plus than the old reef was, the odds would be millions to one, and why would you roll on a risk like that? Huey did, and with the reef now over a metre higher than before, so far it seems to have paid off. The same sadly can’t be said for the best waves in the Hinakos, the outer islands off west Nias. Ex-classic left, Asu is severely compromised, and Bawa, formerly an epic and perfect mimic of small Sunset, as well as a swell magnet, is wrecked. Lagundri could never be good enough for that to be worth it.

[I’d like to make it clear that all of the above conjecture is written specifically in regard to the surf, and is not intended to compare in any way with the losses and hardships endured by locals. It is written with greatest respect to those Indonesians who lost homes, loved ones and lives in the earthquakes of 2004-2005. That being said, through tourism the surf provides a decent livelihood for a lot of locals, and any compromise of surf breaks is bad news for them too.]

“IT IS WRITTEN WITH GREATEST RESPECT TO THOSE INDONESIANS WHO LOST HOMES, LOVED ONES AND LIVES IN THE EARTHQUAKES OF 2004-2005. THAT BEING SAID, THROUGH TOURISM THE SURF PROVIDES A DECENT LIVELIHOOD FOR A LOT OF LOCALS.”

When the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami unleashed its might on Asia, Nias got off fairly lightly. There was some punishment on the west coast, but the tsunami was relatively minor, as was the damage caused by the earthquake. At Lagundri, the tsunami manifest as a slow moving swell of water, like a big tide, and damage was minimal. Meanwhile, the top half of Sumatra had been flattened, and awesome tsunami waves had destroyed whole coastlines around Asia and killed almost 300,000 people. Unfortunately, the Boxing Day earthquake directly influenced the impending earthquake of March 28th. The Boxing Day quake resulted in an alteration of the dynamic stress loading in the subduction zone, transferring it farther south to an area closer to Nias, and increasing the already tremendous geological strain of two immense tectonic plates fighting for supremacy.

The truth about Lagundri is that the place is onshore in the winter south-east trade winds, and it is only the fact that Nias is so far north, about one and a half degrees north of the equator, that saves it. The influence of the wind is less pronounced at this latitude, and you rely on the early surf and pray for the afternoon glass off. You are thankful for days of good winds when you get them, and when they come on tiny or flat days, you snigger jokingly at Huey and his wicked sense of humour. Even onshore though, the set up demands your attention, and has you constantly checking it, wherever you are in the bay. The wave looks seductive from anywhere on the point, or in the water for that matter. You don’t see them, but at any given time there are dozens of eyes glued to the wave, probing, scanning for weaknesses, and especially for gaps in the crowd. Unfortunately this creates the “hourglass effect”. It is a steady rotation, and as soon as the pack has thinned a bit, the eyes are on to it and get out there, saturating the lineup in one hit. The crowd eventually tapers off again, until boom! The hourglass turns once more, as the latest sets of All Knowing Eyes invade the formerly quiet lineup.

The crowd increased steadily after the first week, but the fellas seemed to have no trouble getting waves, and going to town on them. Between missions to Jamie’s spot and another series of reef peaks [we felt like we found ‘em but no doubt they’ve been surfed before; It’s fun to fantasise though] there was plenty of surf, but we couldn’t seem to get that Big Day. There are a lot of hot local surfers nowadays, I honestly lost track of ‘em, they’d be out there then gone, out there again on different, borrowed boards, it was mayhem. Guys like Anton Dakhi, Justin and Alex Buulolo and Rahiel Wau are attacking with an intensity born of having a perfect wave totally wired, as well as being constantly inspired by travelling shredders.

The locals have added a very interesting dynamic to the lineup. When the crowd is not too thick, the time honoured Indo system of taking it in turns works pretty well at Lagundri, especially if a couple of people sit wide and a couple way outside. However, when it gets past a critical point, and a crew of locals are also out there, the system falls apart. The locals enforce a fairly strict Hawaiian style pecking order, and are totally exempt from the tourist order. Tourists settle on either crumbs or use their nous for being in the right spot for sets. The result is a fair amount of friction and frustration in the small take off zone, and the wildcard is consistency. Consistent sets enable any break to handle a lot more people, but unfortunately Lagundri can serve up notorious lulls. If the crowd increases much more than the 30 plus I counted one two foot day, it will be close to farce.

We had almost a two week run of four foot plus days, with a lot of five foot days and a six foot set or two. It eventually backed off again, and when I peered out one morning to see it two-to-three foot and still breaking on the outside, it was more obvious than ever that the reef was different. We were in neap tides now, a part of the tide cycle featuring little variation in high and low tides. Previously at this part of the cycle the reef was covered, but now it was well clear of the water through the full range of high and low tide. Prior to this uplift, on small days the inside would run like a soft Aussie point break, but this section is history. There is still a fair small day option, a series of reforms from the outside break through to the inside. Not what you’d go to Indonesia for but Ok if you’ve run out of books.

It looked like more swell was coming [it always does in Indonesia], so in the meantime we cruised up to the huge bluffs surrounding Lagundri to see a couple of villages. We strolled through remnants of one of Indonesia’s oldest cultures, a megalithic civilisation using stone and bronze a long way back; current theory has the original settlers arriving from the Yunan area in south China around 3500 years ago. From these beginnings arose dozens of different ethnic groups and dialects, a result no doubt of the rugged topography of Nias, mountain and valley forming natural barriers between different villages in the north, central and southern Nias areas. The villages feature big paved squares, with the unique houses lined up on mall like, wide thoroughfares. The houses are built in an original style of Nias architecture, raised, vaulted and barricaded from the ground for military protection, and featuring a v-shaped design of massive 45 degree timber beams at the front, almost like diagonal bracing but made from two foot thick, smooth teak logs. These tie in with other massive vertical and horizontal beams to create a very pleasing, chunky looking gable wall.

At one point, the locals at the unpronounceable village of Bawomataluo started jeering us: “Touriss! Touriss! Touriss!” Hundreds of them were chanting at us with a vaguely menacing air. It was a bit unnerving, and I imagined I was back in the pre-Christian days on this island, when mangani binu [ritual decapitation] ruled and status was measured in enemy skull counts. Marriage required the prospective husband to present the family of his bride-to-be with as many enemy heads as possible, assuming she had enemies. The more the merrier, and a guy who turned in a massive cranial haul was considered the man and got the spoils.

We picked up the pace a bit, and kept going deeper into the mountains to a waterfall we’d heard about. It was a bit of work up hill and down dale to get there, most of it via very rustic but obviously man made steps, embedded along the length of the trail, some of them in some pretty vertical terrain. In the end, the waterfall was more of a swimming hole, but it was a very cosy little swimming hole, surrounded by huge acacias and palms, with good jump rocks and stationary tubes. The little stationary tubes were pretty much the “waterfall” part of proceedings, but all the same it was a nice, cool interlude from the hot and humid trek. Only trouble was, by the time we’d staggered back up through Bawomataluo to get a bemo, we were ready for another swim. Such are the crosses to bear of the hardy adventurer.

Going back through Teluk Dalam on the road to Lagundri, the vehicle horns were blowing in earnest. Sometimes it is almost like mechanical conversation, different tones and intensities of horn passing news or the time of day, blended with the traffic chatter of bemos and trucks and bikes, like a bunch of old metallic moles at a scrap metal yard shin dig… some are sustained, some short, some squeaky, some staccato. All insist they are right. If I lived in Indonesia, I’d just rig my horn up to a two second timer, and let it rip.

The waves had picked up a little, and we had some good sessions at another spot we called Shifty Point. The crowd had grown at Lagundri, and for our last surfs we sought solace with more side trips. It seems like the Indonesia we all took for granted for so long doesn’t much exist any more. The crowds now can get pretty intense, from Timor to Aceh, and the days of just turning up to uncrowded perfection are numbered. There are still empty lineups, no doubt about it, but more than ever you have to work for them. Really work. But don’t despair, just get it while you can. With our recent novel experience of the changeability of Indonesian reefs, what we used to think of as solid and stable isn’t always so, and your favourite reef break may end up only as long lived as a sandbar.

In the middle of the night of March 28th, 2005, an earthquake measuring magnitude 8.7 hit just north of Nias. The redistribution of dynamic stress loading caused by the Boxing Day earthquake was finally manifest via this latest quake. In essence, it was a very belated and complicated aftershock. Hundreds of buildings were destroyed in Gunung Sitoli and Teluk Dalam, with around 1800 people losing their lives. Our friend, Tao, was up at his village, Botohilitano, hanging on for dear life. While the ground shook around him, he had one arm through his window frame and the other wrapped around his young son and daughter, watching his walls shake.

Down at Lagundri, the locals had only just become at ease with being near the ocean again at night. Despite being spared the full devastation of the Boxing Day tsunami, they were aware of what happened in the rest of Asia, and it had taken months of sleeping on high ground at night before they began to feel safe again. When the rumbling started that night, Raffiel, who was one of the original local surfers from Nias, was up in a flash, pulling his kids and pregnant wife out of his losmen and heading up the road to nearby high ground, thankful now for this feature of Nias terrain. But Raffy just had to go back: “All my money in there, fuck brah, I had to get it!”

He bolted back to try and get his cash. It was in a huge strongbox in the front room and he couldn’t get it open. In the moonlight across the bay, Raffy could see the tsunami coming: “Perfect wave brah, about 20 foot face and just coming strong into the point. I trying again to open that thing, but wave is coming, I go ‘Fuck! I gotta get out of here’ I leave the money, run across the grass, the water is already coming, I climbed up on my mandi roof, stayed there all night. Water is up to here — [points to roof line about three metres above the ground] — half my place is gone, my brother’s place gone. When he saw his land later he said: ‘Who stole my losmen?’ But our family were all OK.”

At least a dozen buildings were wrecked in the bay as a result of the earthquake and tsunami, but Lagundri still got off lightly compared to nearby Teluk Dalam, where collapsed buildings killed many people. Tens of thousands of locals were left homeless throughout Nias. Somewhat ominously, there is still a very large, suspect section of the Sumatran Subduction Zone, south of the previous two large quakes, that extends down past the Mentawaiis. The plates here are also straining against each other in a huge build up of pressure and will sooner or later slip to create a megathrust event, the perfect kind of earthquake to produce tsunamis due to the extensive deformation occurring on the ocean floor. For surfers, once again the aftermath will also almost certainly include changes in bottom topography, unfortunately in the world’s most perfect surf zone. Looks like we’ll be trying to beat a Royal Flush this time.

THANKS TO AIR ASIA FOR GETTING THE ENTIRE CREW TO NIAS. FOR SOME OF THE BEST DEALS ON FLIGHTS TO INDONESIA CHECK OUT AIRASIA.COM