This is the story of the first warung in Nusa Lembongan. Or perhaps it wasn’t the first. But true to the nature of such stories, its charm renders us believers, and no one much cares to refute the claim.

It is 1975 – or there abouts – and a nameless, sun-blanched young man hops a Jakung at Sanur, intent on crossing the deep, swirling eddies of the Badung Strait. A jakung is a traditional Indonesian outrigger canoe with a small outboard motor used by Balinese fisherman. He hopes it will carry him safely across the blue abyss, to Bali’s silhouetted sister island, Nusa Lembongan. She has been beckoning from across the sea, bathed in a low-lying mist, keeping her wave-secrets to herself. Yet to be ornamented with hotels and villas, Jungut Batu is a fishing village, marked by squat huts with dirt floors. The floating water park and the charter boats are years away, and the bay is a silent, brilliant blue. Empty waves rise and fall with tide, unseen except by the wistful eyes of a fisherman, returning with his morning’s catch.

Where the sand meets more solid ground there is a hut, made from bamboo with a thatched grass roof. At the open door, sheltered from the hot sun, a young man who will later call himself Jonny – for the ease of the ex-pats – watches as boats move into the bay. Inside the hut, a woman stands over a single flame, on which she fries ikan – fish, fragrant with kemiri, coriander and tumeric.

A white man climbs out of a jakung and wades through knee-deep water onto the sand. The young man has seen some foreigners before, on this island, and heard of their coming and going in Bali in greater and greater numbers. This one carries something long and flat under his arm. He makes his way up the beach to the man’s home, the first obvious port of call. He is broad shouldered, bronze skinned and smiling. He knows a few words in Bahasa, which the man knows, as well as his own island dialect. They exchange words in fractured language, before the white man puts his bag down in the hut and removes the unusual object from its covering. At closer inspection, it appears to be a seafaring craft, made from similar watertight materials as they use in the fishermen’s boats.

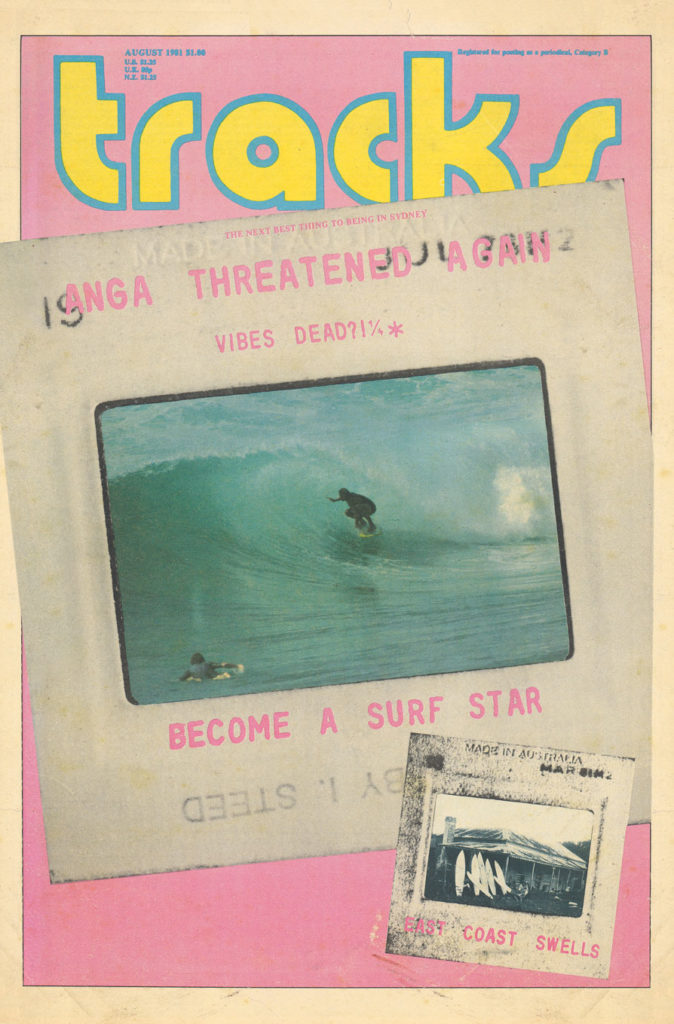

The Indonesian man watches as the white man takes the object under his arm, and runs down to the water’s edge. He lies on its flat top, and begins to use his arms as paddles, impelling himself towards the outer reef, to where the waves are breaking in fleeting bursts of white. He goes to the spot that the fishermen must avoid: the reef’s highest point. Here he begins to traverse the sea. The man watches him return to the same position and repeat the act, covering the same stretch of sea over and over. He seems to have no destination, no objective. Bewildered, the man goes to tell his father – the village chief.

The younger man is curious, and has an idea to follow the white man into the water in the jakung. The chief cautions him against going out to take a closer look, still wary of outsiders after the years of Japanese occupation during World War II. But the young man remembers the broad smile of the visitor, and feels he is not a threat. So he goes, and from his canoe, in the channel beside the reef, he watches as the visitor travels along a wave, drawing graceful curved lines along the its unbroken face. As the wave begins to slow, the white man looks back at his spectator in the channel and lets out a whooping sound, and the young man in the dug-out whoops back.

Some hours pass before the white man makes his way back to shore, his bare skin glistening with salt crystals. He seems even happier now. His smile goes from one ear to the other, and he speaks his words with an energy and a thrill unlike before. His eyes are ablaze. He rubs his stomach, motioning hunger. So the Indonesian man goes to his kitchen and prepares a bowl of rice. He watches as his visitor shovels the food into his mouth with his cupped hand. He is ravenously hungry. He asks for another plate just the same, and the man rises and goes to the kitchen laughing and shaking his head. He has never seen a man eat so much. On the island it is customary to eat only one large meal a day. After another plate topped high, with fish this time, as well as rice, the white man sits back and sucks in a long deep breath. His host watches him intently. He sits now serenely, a blissful look in his eyes, a lazy smile.

Later that evening, after the visitor has gone to sleep, the family talks about the strange white man who traversed the waves. Who returned to their home and ate and ate and was happy, and they laughed and shook their heads. The young man thought quietly that it had something to do with what happened in the sea earlier.

These days we have a name for that: surf stoke. But it must have seemed a little strange to the young island man at the time. His home later became Jonny’s Warung, and later still, Mainski Resort. In 2001, our protagonist, now named Jonny, had taken over his father’s role as the village chief, and wore a traditional check sarong with a t-shirt and a leather jacket, a leather brimmed hat and Italian sunglasses. Like the island itself, Jonny represented tradition and modernity intertwined, a meeting between the East and the West. That year he told the story of the first surfer to visit Nusa Lembongan to a small group of Australians – my mother-in-law included – who have cherished the tale ever since and passed it on to eager listeners.

Who was the nameless surfer who first risked the perilous crossing of the Badung Strait wondering what lay beyond the mirage? I asked characters such as Dick Hoole and Rusty Miller, who were in Bali in those early years of surf travel, but neither could say for sure. Our nameless surfer was one pioneer who never made the magazines or the films. But it makes you wonder how many people were charting unknown territories, who looked for and found their own surfing nirvanas – without the documentation to prove it. Those are the stories of folklore, that exist outside the sphere of photography, of the Internet and Instagram, that bend and twist as they will. Who knows how much they resemble their original selves, and in the end, maybe that doesn’t matter.